Economists are often cheapskates.

Monday, 11 January 2010

"When my wife buys a car, she seems to care what color it is," he says. "I always tell her, don't care about the color." He initially wanted a gray 2007 Mercury Grand Marquis, but a black one cost about $100 less. He got black.

Children of economists recall how tightfisted their parents were. Lauren Weber, author of a recent book titled, "In Cheap We Trust," says her economist father kept the thermostat so low that her mother threatened at one point to take the family to a motel. "My father gave in because it would have been more expensive," she says.

"Where do I begin?" says Marisa Kasriel when asked about the lengths to which her father, Northern Trust Co. economist Paul Kasriel, will go to save a buck: private-label groceries, off-brand tennis shoes and his 1995 Subaru, with a piece of electrical tape covering the "check engine" light.

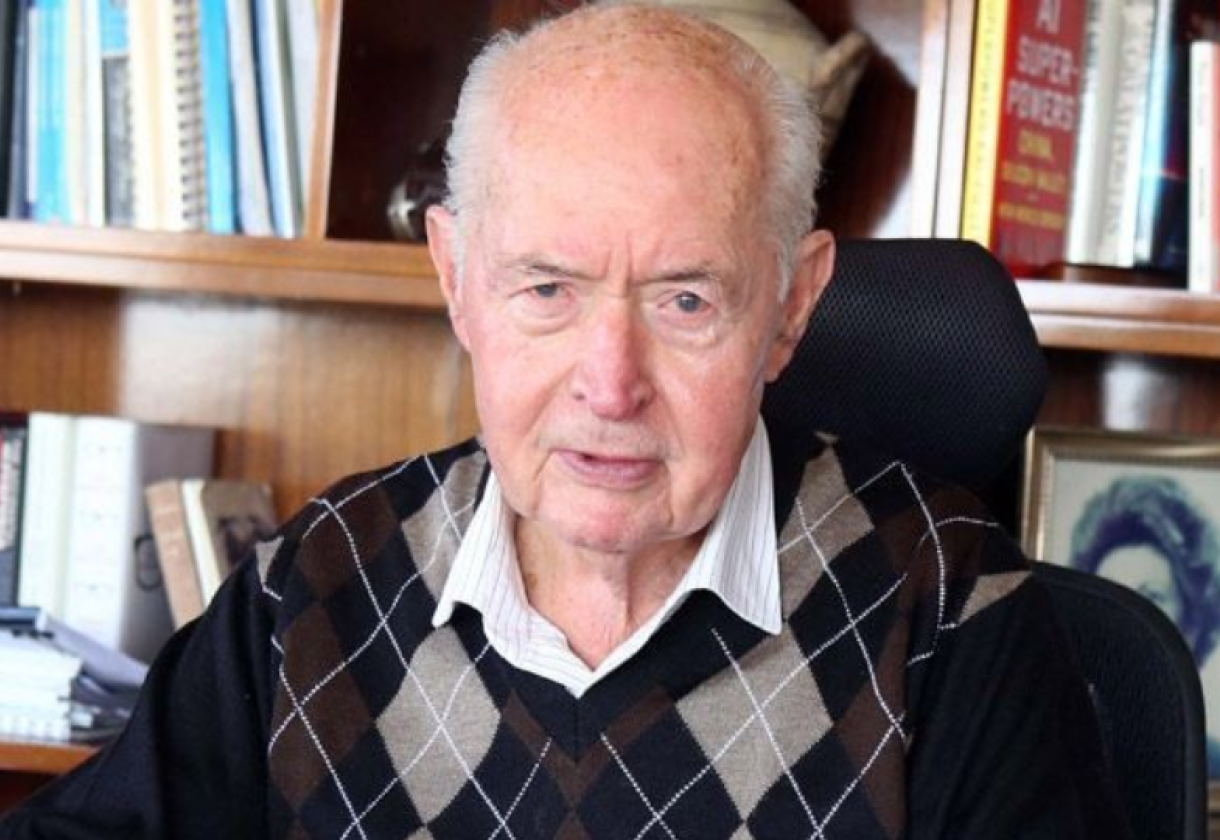

David Colander, an economist at Middlebury College in Vermont, says his wife -- his first one, that is -- was miffed when he went shopping for the cheapest diamond. Economist Robert Gordon, of Northwestern University, says he drives out of his way to go to a grocery store where prices are cheaper than at the nearby Whole Foods, even though it takes him an extra half hour to save no more than $5.

economics majors were less likely to donate money to charity than students who majored in other fields. After majors in other fields took an introductory economics course, their propensity to give also fell.

"You might be an economist if you refuse to sell your children because they might be worth more later."

And the principles that can make economists seem cheap sometimes lead them to hire help, because they are taught to value their own time. "Bob doesn't see why we can't just hire people to trim the Christmas tree," she says. "I tell him that's not what it's supposed to be about."

Given their understanding of the odds of gambling, economists seldom frequent casinos, which is one reason the meeting isn't held in Las Vegas. A decade ago, a hotel sales representative showed Mr. Siegfried a chart showing how little economists gambled compared to other people, he says

One year, Yale University economist Robert Shiller, who'd never gambled in his life, found himself at a casino there. He says that was because Wharton economist Jeremy Siegel realized that by using coupons offered to conventioneers, they could take opposing bets at the craps table with a 35 out of 36 chance of winning $12.50 each. Over two nights, Mr. Shiller netted $87.50.

He hasn't gambled since.

Abstracts from Justin Lahart’s article

0 comments:

Post a Comment